This week I’m dealing with a topic that most quilters love to discuss — fabric. Initially, the plan was to continue estimating fabric for an on-point quilt. We just finished up the process with a horizontally set quilt, and it was natural to just jump to the next step and deal with setting triangles. However, as I read back over those two blogs, I discovered something: That was a lot of math. And even though it was pretty simple stuff, there was a lot of numbers tossed around. I realize while math doesn’t really bother me much, I’m could be in a minority. So, while we will “math out” an on-point quilt next week, this week, we’re taking a break from number crunching and will talk about fabric – more specifically your stash.

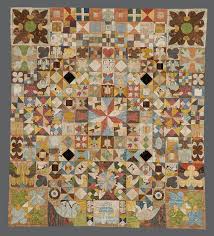

I’ve quilted for nearly 34 years. In that 34-year time span, I’ve been to a lot of quilt shows, shop hops, and quilt/fabric stores. I’ve inherited stash from quilters who have passed away or had to stop quilting. I have bought serious inventory from quilt/fabric stores going out of business. Yet, by some quilters’ standards, my stash is modest (for those of you who aren’t acquainted with the word “stash,” it’s the extra fabric quilters hoard store to use later). I know some quilters that have floor-to-ceiling-come-to-Jesus stashes. I’m not one of them despite what my family says. The last quilting statistics I read about such stockpiles suggested the average fabric stash is worth about $6,000.00. And I believe every cent and yard of it. Fabric has become more expensive in the past ten years because world-wide cotton crops have not done well. One of the reasons I love to go Lancaster, PA is the range of quilt shops there and the reasonable prices. I can pay for the trip in what I save in fabric.

I do try to carefully cultivate my fabric. While on occasion, I will come across some fabric I just love and will purchase the entire bolt, that is the exception and not the rule. Through the years I have developed a purchasing plan for my material. This plan allows me to use what I purchase regularly and keeps me from busting my budget. And nothing gives me a bigger thrill than looking through my stash and finding everything I need to make a quilt.

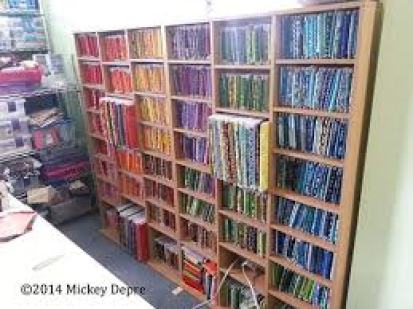

The very first thing that must be considered when cultivating your stash is your storage space. When I began quilting, my sewing machine was in my kitchen because that was the only space available. The house we lived in then was much smaller than our present one and had no extra rooms. This was actually an ideal situation because my daughter was just a few months old and the location allowed me to keep an eye on her while she played in the family room (which was literally three feet away), and gave me access to our kitchen table (where I cut everything out). But this set-up meant my storage space was limited to two file drawers and one cabinet. My time was also limited, between having a small child and a job. Fat quarters became my go-to fabric purchase because I only made small projects due to time and material limitations. These took little storage space and I could procure a wide variety without breaking my budget (which in the mid-eighties was admittedly tight). If your storage space is small, you may want to limit your purchases to fat quarters or other small pre-cuts or to only the amount of fabric a quilt pattern calls for. You don’t want to over run your storage space. This makes it difficult to keep it organized and hard to see what you have. Nowadays, my storage space is much bigger – I have a large studio and a storage closet – so my stash is greater. I store fat quarters and up to one-yard cuts on small bolts and my flat-folds are stacked on shelves. Fabric destined for a particular project is kept together in boxes along with the pattern and is labeled. This works for me – and it’s a process I came to after years of trial and error. Survey your storage area and research a plan that will work for you.

After you’ve mapped out your storage area, the next issue to wrangle is what to buy. The longer you quilt, the more opportunities you’ll have to go to fabric sales and shop hops and participate in fabric exchanges. Quilt shows – especially large ones – are easily overwhelming. If you don’t go in with a plan or a pattern, you may end up coming home with material you’re not sure what to do with, so it ends up in the back of a drawer or closet. If you shop with a pattern, it’s easy to come away with what you need. But if you’re in a situation when you don’t have a pattern in hand or you’re just not sure what to buy, it’s always great to have a purchasing strategy for two reasons. One, you won’t overspend on fabric you won’t necessarily use, and two, if the sale is a really good one, you will invest minimal cash in resources that will be used to its fullest capacity. It’s this second reason we’re focusing on with this blog – what I call investment fabric resourcing. Listed below are the types of material I purchase regularly when presented with a fabric resourcing opportunity:

Solids

Admittedly, solid fabrics are not my favorite. I like prints because they give movement to a quilt. However, solid colored fabrics make up the backbone of quilting and quilt shops. One of the first pieces of information I pass along to beginning quilting students is to obtain a color wheel – either a physical one or one on their phone.

Use this tool to help you purchase solid fabric. For instance, if you’re at quilt shop or purchasing from an on-line site, and they have all of their solid green fabrics on sale in March for St. Patrick’s Day. It’s a sale you really can’t pass up, because it’s all $3.99 a yard. But you’re not sure what color to purchase with the green fabric for a quilt. If you take a color wheel and find the greens, you will see yellow and blue are next to it and reds are across from it. All of those colors will work with the greens. The colors on either side of the color you’re considering and the one directly across from it will harmonize together.

Another good suggestion is purchase some of your favorite colors. This sounds like a really simple idea – and in many ways it is – but it’s a good thought to keep in mind. If you’re making quilts, you’re going to find a way to work in colors that appeal to you. For instance, I can count on one hand the number of the quilts I’ve made that have a lot of brown in them – approximately three. But purple? I work it into every quilt I can. Same thing with blues, pinky-reds, and yellows. Buy the colors that make you happy and I can guarantee you’ll use the fabric up.

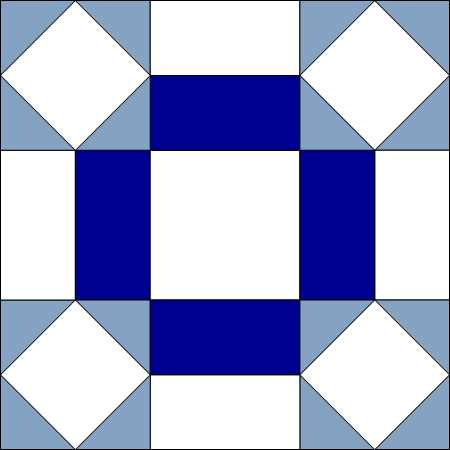

One of my favorite ways to use solid colored fabric is to utilize it as the “zinger” fabric. In most quilts I make, there’s one fabric that’s used to give it a little extra “sparkle.” Nine times out of ten, I use a deeply saturated solid fabric for this. It’s used sparingly and evenly over the quilt top, usually in smaller patches where a print would lose its integrity because the space is too small to frame it.

So, when I get a chance to shop for solid fabrics, I use a color wheel and look for my favorite colors in deeply saturated tones. With this in mind, let me introduce you to my favorite solid colored fabric line: Painter’s Palette by Pineapple Fabrics.

I love this fabric more than Kona. It pieces like a dream, but it’s so soft that it’s wonderful for hand applique or hand piecing. If you’re interested, you can find it at Pineapplefabrics.com. I recommend you order their color card – it’s exactly the color of the fabrics. I’ve never been disappointed

Backgrounds or Neutrals

Let me state this first and get it out of the way: I realize that nowadays, what’s considered a background or neutral can be nearly any color. I acknowledged that about seven years ago when the Best of Show at Paducah used bright yellow as the neutral. However, for this blog, we’re using the term neutral and background in its purest forms – all varying colors, shades, and hues of beiges, ecrus, grays, blacks, and whites. If you’re at a fabric sale and can’t find anything you need or like, you can’t go wrong with a few yards of a neutral. Neutrals and backgrounds will always be used.

Personally, my favorite background or neutral always has either tone-on-tone or a fabric with some kind of background figures. Solid ones almost look too stark (in my opinion), unless you’re making a modern quilt or an Amish one.

Another background or neutral you may want to add to your stash are the low-volume fabrics. These are generally neutral colored fabrics that have another colored figure printed on them, but the spaces between the figures is fairly large and the print is so small that the material “reads” solid (looks solid from a distance). Low-volume neutrals are quickly becoming my favorite neutral.

Prints

Prints are my favorite quilting fabric. They offer color and movement, in addition to nearly endless variety. Prints fall into four categories:

Small Prints – These prints are so small that they they can almost look like a solid from a distance. The above print is too colorful to appear as a solid.

Medium Prints – I tend to categorize these into fabrics with designs that are no larger than a quarter.

Large Prints – Fabrics with prints that are larger than a quarter. These are typically used in border work, but if you have large blocks with large units, they work great in those. What’s even more fun is when you can fussy cut a large print to use in a block unit.

Blender Print – I love blender fabric! It’s just so versatile. Loosely defined, blender fabric is a tone-on-tone fabric (though typically not a traditional neutral), that can pull two or more of the quilt fabrics together. It can look like a solid from a distance, or it may offer a bit of contrast, although the colors will be in the same family. I like them because they tend to give movement to a quilt.

Within these four categories, you will probably want to have some of the following: Polka dots, checks, plaids, geometric prints, stripes, and florals. I have found that stripes and checks really make interesting binding, especially if they’re cut on the bias.

Holiday Prints

I put holiday prints in a separate category from “regular” prints because not everyone purchases them. I am one of those people. While I do have a few Christmas, Halloween, and Easter prints, I tend to purchase colored fabric that reminds me of the season (greens, reds, blues, blacks, acid greens, oranges, purples and a bevy of jelly bean colored material). I’ve never been one to buy yards of fabric with Santa Claus, Jack O Lanterns, and the Easter Bunny on them. In my mind, the seasonally colored fabric could be used even after the season, where as any material with a direct holiday print would be limited in use.

However, if you’re one of those folks that love holiday prints, let me caution you to keep this collection balanced (small, medium, and large prints, as well as blender fabric). I would also keep this group small in comparison with the rest of my stash, since it is really limited in its use.

Precuts

To have or not have precuts in your stash is a personal choice. Some quilters love them and others…not so much. When they first began to appear on the shelves of my LQS, I was skeptical. I finally (after much thought and internal debate) did purchase a jelly roll on sale and brought it home to try.

And was completely underwhelmed. While the fabric selection was stellar, I found the cutting to be inaccurate. Not all the strips were exactly 2 ½-inches, and some were off as much as a quarter inch. But fast forward to 2020, and it’s a completely different ball game. The cutting is accurate (for the most part), the selection is through the roof, and there’s a great deal of variety – charm squares, layer cakes, jelly rolls, cinnamon buns, mini-charms.

If you find yourself increasingly cutting 5-inch squares or 2 ½-inch strips, you may want to consider adding these precuts to your stash. If you like patterns that call for precuts, definitely add them to your stash as you find them on sale and in the colors you want. However, if you’re not sure where you stand on precuts, then I would hold off. If you find a pattern that calls for 2 ½-inch strips of a neutral, you may find it a better budget deal to purchase a jelly roll in neutrals rather than buying yardage of several different ecrus, grays, or whites. I personally have found doing this is less expensive and a time saver – no cutting involved.

Personal hint here: I’ve always found jelly rolls to be “linty” when they’re unwrapped. To avoid hundreds of stray threads all over my floor and sewing machine, I’ve learned to open them outside and run a lint roller over the top and bottom of the roll before I begin to sort the strips. While this won’t get rid of all the lint, it does go along way to dispose of most of it.

With all of these in mind, how do I know how much to buy to build an effective stash?

This question has several issues to consider, and even then, there’s no really right answer. Most of it has to do with you, your quilting space, and what kind of quilter you are. When you’re purchasing fabric for a quilt, it’s really easy to round up the yardage and purchase “just a little bit extra” – round that half a yard up to a yard, etc. So the first two concerns to be addressed concern money and space – can I afford the extra fabric and do I have space for it? It makes no sense to bust your budget and it’s equally unwise to overflow your storage space. If you can’t afford it and/or don’t have a place to put the extra, the answer is “No” – don’t buy the additional fabric.

But … if you have the money and the storage space, you should ask yourself, “How much do I love this fabric?” I truthfully have used a fabric I’m not crazy about in a quilt simply because it worked well in the color scheme. Given a choice, once that quilt was done, I would never use or look at that fabric again. This would not be a wise choice for my stash. If, in the process of purchasing fabric for a quilt, there is a blender, solid, focus fabric, or print that you love, a half-a-yard extra or so would be a good addition to your stockpile.

If you’re not purchasing material for a quilt, but simply shopping a sale, it’s always a good idea to bulk up on traditional neutrals, solids, and blenders – especially in the colors you love. It’s also a wonderful idea to inventory your stash before you go to a sale – not a hard review, but know what areas are lacking. If you need blenders, shop for those. If you need small prints, look for those. My yardage suggestions are just that – the guidelines that work for me. If I’m purchasing for my regular quilting stash, I will buy between one and three yards. Since I applique, I’m constantly on the look out for fabric that will work well for flowers, leaves and vines. For material with applique potential, I generally buy one-yard cuts.

However…with focus fabrics or that once-in-a-great-while event when I fall head over heels in love with a print, I purchase five yards. Why five? Two reasons – no matter what size quilt I make, five yards will cover the yardage need and probably the binding, too. The second reason is a manufacturer will rarely ever re-print a line of fabric once it’s sold out. Buy it now or regret it forever. And if I love it enough to buy five yards, I will quilt it all up, I promise.

To sum it up, you’re the one that will have to determine the size of your stash and what it consists of. The type of quilter will also play into this – do you only piece or do you applique, too? Do you make primarily bed quilts or wall hangings or small quilts? Those characteristics play into the size and monetary value of your stockpile. I encourage every quilter who has fabric storage room, to balance that stash and shop wisely: Have a list, shop local, use sales and coupons. But I also will leave you with this – if you see a fabric you love, just buy it. Pay full price and have no regrets. Life, as it has shown us lately, is too short to wait on some things.

Until next week, Level Up Your Quilting!

Love and Stitches,

Sherri and Sam