Sewing machines … even the most basic ones … come with a lot of stuff you may not know what to do with. I faced this situation today. My daughter and son-in-law decided to homeschool the grand darlings this year. Before I get a ton of questions and comments about homeschooling (all the good, the bad, and the ugly), let me inform you this decision was made after a great deal of thought. Last year, they were enrolled in a wonderful charter school, but with COVID pushing back in-person instruction here for at least the first nine weeks, and the learning portals having good days and bad days (they were down three out of the first five days of school), it was decided homeschooling would give the girls more consistency. And, as a retired educator, I agreed.

I am delighted that my daughter and son-in-law let me part of their curriculum. For one hour every week I get the girls for sewing. My oldest granddaughter has a sewing machine, but I had to buy the youngest one. We settled on a Juki. It’s a very basic machine with a finger guard. However, I was pleased to find it not only had several decorative stitches, it also came with a drawer of stuff – seam ripper, oil, needles, an extra spool holder, and two extra feet. One is an open-toe foot and the other is a walking foot.

Which totally threw Ellie for a loop. “What’s this?” she asked, holding it up for my inspection.

“It’s a walking foot,” I told her.

“Doesn’t the machine need two so it can walk?”

After I explained what a walking foot did (after I choked back my laugh), it still made no sense to Ellie. That doesn’t bother me. One day it will become apparent what the foot does and why it’s important, but it got me wondering just how many of us have a walking foot and are you aware of just how many things it can do?

Most walking feet look a little like this:

You remove whatever foot you’re using on your machine and attach this foot. Wikipedia defines a walking foot as this: “A walking foot is a mechanism for feeding the workpiece through a sewing machine as it is being stitched. It is most useful for sewing heavy materials where needle feed is mechanically inadequate, for spongy or cushioned materials where lifting the foot out of contact with the material helps in the feeding action, and for sewing many layers together where a drop feed will cause the lower layers to shift out of position with the upper layers. A walking foot is also good for sewing materials with varying layers because it can climb up and down these layers easier than other feeding mechanisms.”

And if you think this definition makes the walking foot sound like a tool every quilter needs, you’d be correct. But more on this a little further down in the blog.

With almost any sewing machine, the fabric is moved by the feed dogs.

The presser foot holds the fabric down and as the feed dogs move, they take the fabric with it. It is actually moving the lower fabric that is sitting on the feed teeth and the upper piece of fabric is just going along for the ride. This is why, at the end of stitching with a “regular” presser foot (such as the ¼-inch quilting foot), the two fabric pieces maybe mismatched a little or a lot, depending on the type of fabric that’s sewed.

At this point, it’s important to reference the difference between a walking foot and dual feed. While it’s possible to find a walking foot/walking foot attachment for almost any make and model of machine, not all machines have dual feed. However if your machine comes equipped with dual feed, it works in tandem with a walking foot. So, what is dual feed? Dual feed is the machine’s ability to feed the fabric through the top and bottom at the same time – both fabric layers are fed evenly over the feed dogs. This keeps the fabric from crumpling or shifting. Why is this feature so awesome? Well, if you like to incorporate plaids, checks, or ginghams in your sewing projects, this keeps everything lined up, so nothing gets off kilter. Likewise, if you sew complicated quilts with lots of layers or work with machine applique, you quickly learn to appreciate dual feed. If your machine comes with this feature, it will probably be listed as one of the selling points either by the salesperson or in the sales brochure. If you’re still not sure, consult the all-knowing Google (put your machine’s make, model, and number in the search bar) or the machine’s manual. Either one should be able to tell you if your machine is dual feed equipped.

While the majority of my machine’s feet simply snap on, the walking feet work a little differently. In order to engage the dual feed mechanism with the walking foot, I attach the foot by inserting the dual feed bar in the back of the foot.

If you have both the walking foot and dual feed, it truly is a wonderful thing because:

- The walking foot moves all fabric layers at the same time and pace according to the feed dogs. The dual feed function affects the top layer of fabric and the feed dogs control the feed of the bottom layer of fabric. If you have both working in tandem, then you’ve lowered the possibility of the fabric shifting any to pretty much zero. If you quilt any of your tops on a domestic machine, you quickly learn to appreciate this feature. The top, batting, and backing all stay together, move through the machine at the same time, and reduces the chances of any puckering.

- The walking foot has no motor and the foot is dependent on the feed dogs’ movement. This action moves all the layers at one time. Once the walking foot gets to the back, it lifts and springs forward, and waits for the next feed dogs’ stroke. The dual feed mechanism has a separate motor so the top fabric (that can get somewhat left behind with the walking foot), keeps up with the lower piece of fabric. Anything in the middle (like batting), just hangs on for the ride and moves with the top and bottom fabric.

I purchased two alternate walking feet to go with Big Red. There’s this one:

It looks very much like the standard walking foot, except for the black phalange on the right side. This is the ¼-inch walking foot, which works just like the quilter’s foot:

I line the fabric up so that it’s touching the black phalange on either foot and I sew a perfect ¼-inch seam. This is great for piecing blocks that have a lot of layers coming together at one point, so nothing shifts out of place. I piece with this foot at least 90 percent of the time. If I’m quilting a top on the machine, this phalange acts as a guide if I want to stitch close to the block seams, but not actually in the seam.

Recently I purchased this walking foot:

It’s an open-toe walking foot that I can use with machine applique. It works great with either a zig-zag stitch or the buttonhole stitch and prevents any lower layers from shifting.

Regardless of whether or not your machine has dual feed, you should give your walking foot a lot of use. I realize my blog primarily concerns quilting, however; if you make garments, a walking foot can save your sanity when sewing plaids or checks – it really keeps them lined up nicely. Likewise, if you’re sewing lingerie, undergarments, swimsuits, or anything else with straps – it keeps everything in place. I have also heard the walking foot works well with knits and other stretchy and slippery fabrics that easily shift.

Both quilters and garment sewers make projects with lots of layers – like bags, totes, and wallets. Those types of projects tend to take not only lots of layers of fabric, but also thick, sew-in interfacings. A walking foot can help keep all those layers together and prevent any shifting.

And as for quilters, I really recommend using a walking foot for sewing on the binding. At this point in my quilting career, I can’t imagine using anything else. When sewing on the binding – especially if you’re using the traditional French Fold binding – you realize that your joining six layers of fabric together – the backing, the batting, the top, and two layers of binding. That’s a lot of bulk and with a traditional foot, even with the dual feed, it’s easy for all of that to slip out from under the needle. A walking foot, especially if it’s working in tandem with a dual feed, largely prevents this from happening.

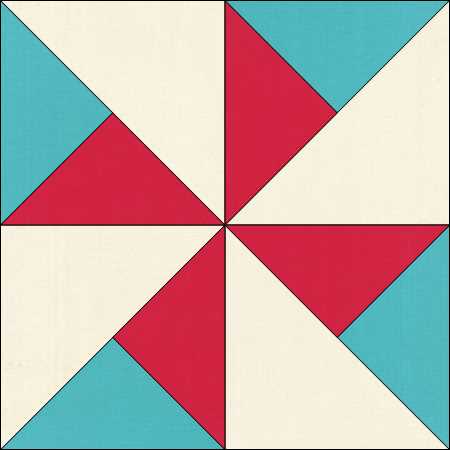

If you quilt any tops on a domestic machine, some quilting can be done with your walking foot instead of dropping those feed dogs and quilting that way. If I’m working with a lot of straight-line quilting (such as cross hatching) I’ll mark my lines and go at it with a walking foot. Quilting which incorporates gentle curves such as this:

Or this little table topper I made:

Can be made with a walking foot. I draw my quilting lines out and then just follow them.

A walking foot is a great attachment to have, and it can be used for lots of different types of sewing. However, keep in mind that as great as this foot is, it can’t be used for everything. The walking foot handles some zig-zag stitches pretty well. Others not so much. I’ve learned mine handles a “traditional” zig-zag (one swing left and one swing right) great. If I’m incorporating a zig-zag which has multiples swings to the left and then the right, it doesn’t handle that much side-to-side action well at all. I use a regular presser foot for that type of stitch. Likewise, the decorative stitches that have a lot of right-to-left movement or forwards and backwards movement – most walking feet can’t make those stitches. It was made to move in a forward direction.

I hope this blog encourages you to get your walking foot out and use it more. It’s a great little attachment to have. If your machine doesn’t have one, jump on the internet machine and Google your make, model, and machine number to find out if it’s a high shank or low shank. Then Google walking feet. You should be able to find a generic one that will work on your machine. And they’re not super-expensive.

Until next week, Level Up Your Quilting!

Love and Stitches,

Sherri and Sam